Diana Sudyka began her art career creating gig posters for musicians such as Andrew Bird, St. Vincent, The Black Keys, Iron & Wine, The Decemberists and other bands. She has also illustrated several volumes of the award-winning children’s book series The Mysterious Benedict Society by Trenton Lee Stewart. When not working in her studio, Sudyka volunteers at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Her life-long interest in natural history is reflected in her distinctive paintings, which she editions as prints.

I had the chance to talk to Sudyka about how art and nature come together in her work.

BR: Your art explores the poetic side of natural history—things like the wild intelligence that enables birds to navigate by the stars and the way the changing seasons influence our psyches. How did nature come to be such an important part of your work?

DS: I have lived in a very urbanized environment for over 15 years. But my early years were spent in much more rural environments, and those places and the types of experiences that go along with them still define me. I believe that every child is born with a strong sense of biophilia. I held onto mine, and sought out nature even in urban environments. As a result of my connection with nature, I became a keen observer of the natural world, and learned much about our local flora and fauna, and their cycles in relation to the seasons. All of this finds its way into my art.

BR: Your work has a strong narrative aspect to it, in part because you often incorporate text in your work, by painting phrases directly onto your paintings. Your fans love the words in your paintings and often purchase prints based on your text as much as your imagery.

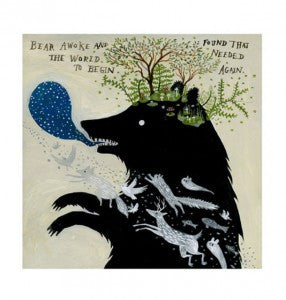

One of my favorite lines of yours is “Bear awoke and found that the world needed to begin again.” That phrase simultaneously feels like an opening from a fairy tale and a spiritual aphorism. We have all had days when we woke up and felt like the world needed to start over.

What inspired you to make text a part of your visual work, and what role does language play in your creative process?

DS: The first illustration jobs that I worked on were screen-printed gig posters for bands. I hand-lettered all of the text in those posters, and developed a love of uniting image and text, especially hand-lettered text. This carried over into my paintings. I also have a deep love of narrative and children’s picture books, and this influences my work as well.

BR: Some of your paintings have a poignant environmental message. For example, “He Was Ready to Follow” presents a polar bear on a shrinking iceberg, surrounded by other arctic creatures that seem to be swimming away. Painted into the image are the words, “He knew that once the ice melted, he would be ready to follow where they were going.”

What are your thoughts about the role of art in conservation?

DS: I believe that using art to address ecological issues is important. Art can be an effective way to raise awareness and also provide healing. I also believe that there is a type of grieving specific to the experience of ecological loss. I experience it for sure, and have seen it in others, too. My work serves as a means for me personally to try to come to terms with that loss, but I also hope to raise awareness about what is going on with the environment and climate.

Paintings like “He Was Ready to Follow” or the “The Migration” are stemming from a sense of loss over the melting polar ice, and its implications for the animals that live and depend on those ecosystems. Things are pretty grim right now, but I try not to give into despair, and part of not giving into despair is finding a way to work through it. For me, that means addressing it in my art.

BR: The first print of yours I saw was “Star Map,” which depicts two birds in a nest with a star map overhead. I know that the inspiration for this print came from your volunteer work at the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History, where you overheard an ornithologist explain how some birds use the stars to navigate their migration routes. Are there other paintings that were inspired by your time at the Field Museum, and what inspired a few of those?

DS: I can’t think of an additional example quite as specific as the one you provided. In a more general sense, my experience at the Field Museum was the main inspiration behind starting my Tiny Aviary blog. Tiny Aviary began as a space to document and learn about every bird species I worked on in the Chicago Field Museum’s bird lab. That is how it began, but it grew into more, and that in turn influenced themes I addressed in my paintings.

BR: What aspect of natural history most intrigues you?

DS: I love the tradition of art documenting nature, and the technique traditionally employed to make those images: intaglio. My foundation is in intaglio printmaking. I still see myself as a printmaker even though it has been awhile since I have been able to make images that way. I have a deep love for the engraved and etched images made by early naturalists like James Audubon, Alexander Wilson and others. Their main purpose was to catalog flora and fauna, but there is so much visual richness and beauty in those engraved plates.

BR: Another recurring theme in your work is a delightfully quirky sense of humor. In your painting, “The Backpack,” birds are stealing the content of a hiker’s backpack, and your text reads: “The Stellar’s Jays were the first to spot the bag, lying in the moss and ferns. They carefully removed the contents, passing objects up the tree one by one. They worked quickly, not knowing if or when the owner would return.”

Was this inspired by what you learned about the mischievous behavior of the jays at the museum, or personal experience?

DS: Both. Corvids—the family of birds that includes crows, ravens, rooks, magpies and jays—are extremely intelligent and resourceful. I have been fascinated for a long time, and I read books about them by the great naturalist, Bernd Heinrich. Also, I have camped quite a bit in the Pacific Northwest, and I have firsthand experience with the bold antics of Stellar’s Jays at campgrounds.

BR: A few of your paintings have a dreamlike quality. In the painting, “Stately Grace,” the following phrase is worked into the imagery of an antlered creature stepping over a tiny village: “It moved with stately grace as it stepped over our house. They didn’t believe me, but I knew it was real.”

Can you tell us what inspired this painting?

DS: Just that feeling that maybe we cannot—or should not—always try to explain everything. If you experience something that others might not believe or understand, this doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen or it can’t have a profound effect. Basically, it’s about embracing the mystery.

Click here for available prints by Diana Sudyka.